A Part of Me Didn't Want to Write This Article

But other parts of me did, so I decided to do it. And there you have an introduction to Internal Family Systems (IFS), a powerful approach to working with inner subpersonalities. If you are familiar with therapeutic models such as Psychosynthesis, Transactional Analysis, Hal and Sidra Stone's Voice Dialogue, or "Look Who's Talking" used in Barbara Findeisen's STAR program, or concepts such as internal objects or schemata, you have an idea of how this works. In the chapter on integration in their new book, Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy, Stan and Christina Grof mention Voice Dialogue and offer a good explanation:

Their technique allows us to dialogue with our inner selves and discover how they operate within us, how they feel, what is their hierarchy of values, how they make us feel, what they want from us, and so on. By bringing awareness into different facets of ourselves, we can reach the state of the Aware Ego—experience our selves as separate from us and "unhook from being identified with a particular self." (p. 107)

Besides being grounded in the "parts" perspective like the above approaches, Dick Schwartz, the founder of IFS, has developed a cartography of this inner world and a protocol that allows us to work very effectively with the parts. He views the parts as falling into three categories: exiles, managers, and firefighters.

Exiles are the parts that are kept out of consciousness, in the shadow. They tend to carry difficult feelings such as vulnerability, helplessness, neediness, and terror, but they also bring innocence and joy. Managers are generally protector parts that take on the job of keeping the exiles safely locked away, to protect them and to protect the system from them. When we don't feel the exiles, the managers assume that everything is OK. Some managers are focused on helping us get along with others and function effectively in the world. When protective managers are not completely effective and exiles threaten to take over the system, firefighters spring into action. These parts will get us to do anything to disrupt the emergence of the exiles. Rage and addictions are typical firefighter strategies. Managers and firefighters repeat these dysfunctional behaviors because they are compelled by "burdens" they took on to protect the system at an earlier time. For example, a part could watch a young child be repeatedly rejected and take on the burden of protecting the child by making sure the person never speaks up. Exiles carry burdens too, but these are usually just negative beliefs about themselves rather than particular jobs.

You may be wondering if these parts are "real." Who knows? From years of working with parts using this model, and earlier in the context of hypnotherapy, I have found it comfortable and useful to treat them as real. They seem to me like the characters in The Matrix—subroutines with personalities and physical appearances. Those of us used to treating archetypal energies and experiences as real should find it natural to do the same with parts. IFS is also open to the possibility of transpersonal parts, calling the beneficent ones guides and the malevolent ones critters.

Along with the parts, we all have Self. I see Self as having a personal and a transpersonal aspect. On the personal side, Self takes care of the parts by listening and responding to them. Like a good parent, Self has compassion, acceptance, and interest in all the parts, providing leadership and making decisions for the system that are advantageous and as fair as possible to all parts. The transpersonal aspect of Self brings awareness of our unity with the divine.

My first experience of IFS was a brief practice session at a workshop. My "therapist" asked me how I felt toward a part that I had selected to explore. Each time I provided a response that indicated the attitude of another part rather than Self, for example, annoyance or intimidation, she asked if that part could step aside. After three or four such interventions, I spontaneously took a deep breath and found myself feeling compassion, acceptance, and curiosity toward the target part. I was in the experience of Self, not by virtue of some spiritual practice, but simply by repeatedly asking each part that arose to step aside until Self was revealed. How exciting to find a completely new path to the experience of Self!

IFS therapy promotes "Self-leadership." To achieve this, it offers techniques to unburden parts and to retrieve exiles from where they are stuck in the past. As the parts release burdens, they are less likely to "blend" with Self and try to control the person's behavior. Polarizations between parts are made less extreme, and the parts become more cooperative. An analogy I use is a car, with Self in the driver's seat and all the parts in the back. Normally, polarized parts try to protect their interests by ejecting their opponent from the car and gaining control of the steering wheel. Inevitably, the ejected part returns and grabs the wheel itself in an attempt to prevent further banishments. Think of all the examples (food, anger, striving, people-pleasing, etc.) where we restrict or control for a period of time, until the polarized part takes over, and we completely lose control. When there is Self-leadership, Self listens to the parts in the back seat and tries to meet their needs in a fair way; in return, the parts begin to trust the Self's leadership and find contentment in the back seat, allowing for effective driving.

A tenet of IFS work is to respect the needs and functions of managers and firefighters. As these protectors are completely dedicated to their tasks, we don't expect them to stand down until they are ready. We sometimes request them to step aside and grant us access to exiles or polarized parts, but we never push or insist. With the assumption that the protectors are well-intentioned, we help them release their protective burdens and see that exiles can be safely and effectively cared for by Self. We know that protectors will relax once they understand that it is safe to do so. This respect for defenses creates a huge amount of safety in the work.

To give you a flavor of the process, here is what might be a typical exchange between client and therapist:

A Typical Client-Therapist Exchange in an Internal Family Systems Session

Client: I'd like to work on my bingeing.

Therapist: OK, can you find the part of you that gets you to binge?

C: I don't know. I can sense an agitation.

T: Where do you feel this agitation in your body?

C: In my solar plexus.

T: Can you tell me more about the feeling?

C: It's kind of jumpy and pushing.

T: Can you relate to this feeling as a part that gets you to binge?

C: I guess so.

T: How do you feel toward this part? [If the therapist is talking to Self, the answer will be something along the lines of compassion, curiosity, and/or acceptance.]

C: I need to get rid of this part; I gained 20 pounds in the last two years.

T: So there are parts of you that hate the bingeing part and want to get rid of it?

C: Yeah, I guess.

T: And it makes sense that they would feel this way, right?

C: Yeah.

T: See if you can let them know that, and then see if they would be OK if they went into the waiting room so we could talk to the bingeing part. [The parts can only be helped by Self, and the presence of polarized parts will impede the process.]

C: OK, they said they would do that.

T: Great. So check again—how do you feel toward the bingeing part?

C: I'm kind of scared of it; it has so much control!

T: So there are parts of you that feel like they have less power than this part?

C: Yes.

T: See if they can wait in the waiting room as well.

C: OK.

T: And how do you feel toward the bingeing part now?

C: Kind of sad.

T: Sad because of what it does to you, or sad for it, like compassion? [If the former, we have another part; the latter indicates the presence of Self.]

C: Yeah, compassion because it feels like it has to do that.

T: And you feel somewhat accepting toward this part now and perhaps curious to know more about it?

C: Yes.

T: Great. Ask the part, "What are you afraid would happen if you didn't get me to eat at those times?"

C: It says I can't handle it.

T: Can this part show you more about what it thinks you can't handle?

C: It's like a big endless pit.

T: See if the bingeing part would be willing to step aside for a little bit so that we could find out more about that pit. We'll be careful so that you don't fall in.

C: It's not sure about that, but it says it will try.

T: That's fine. It can watch us and come back if it feels it's necessary. [We want to respect the needs of managers and firefighters to prevent the emergence of exiles.] So can you tell me more about that endless pit?

C: I'm sure it has to do with my parents not being there when I was little.

T: OK, is it possible that there is a part here that is good at figuring things out and knowing the answer?

C: Yeah, I have that.

T: See if you can appreciate that part for how it helps you, but see if it will wait in the waiting room while we get to know the "pit" feeling. [The therapist serves as a "parts detector."]

C: OK.

T: So, just take some breaths and become aware again of the pit feeling.

C: Yeah, it's like a black hole in my belly.

T: Could we relate to this black hole feeling as a part?

C: Yeah, that makes sense.

T: And how do you feel toward this part?

C: I feel sorry for him. He's so alone!

T: Yes. Can he show you a scene where he is stuck in the past? [If the client assigns a gender, then the therapist goes along with it.]

C: He's in his room, and mom is home, but she is sick, or maybe drinking.

T: Would you be willing to go back into that scene and be there for him, however he needs you to be?

C: That seems like a bad idea.

T: Why?

C: I don't think I would ever get back.

T: So there is a part of you that is afraid the little boy will take over if you get close?

C: Yes, that's what happens sometimes.

T: Tell this part, if it would step aside, that we'll make sure the little boy doesn't take over.

C: OK, it's not sure if it can trust that, but it will give it a try.

T: OK, thank that part for being so willing to help us with this. Ask the little boy if he would like you to come into the room with him.

C: Yes.

T: Tell him that you would like to come, but he has to promise not to blend with you. If he tries to blend and take over, you will have to leave. [Addressing the concerns of the part that just stepped aside.]

C: He says OK.

T: So, go back there and be with him. What does he need?

C: Mom treats him like he's worthless.

T: Would he like you to help with that?

C: Yes, but he doesn't know what to do.

T: Ask him if he wants you to talk to mom.

C: He says "No." [Self can intervene directly, or just provide nurturing and reassurance for the exile.]

T: What does he need from you then?

C: Just to tell him that he is not worthless.

T: OK, just be with him in this room, and tell him what he needs to hear.

C: You are fine. Mom has problems, but that isn't about you. I wouldn't leave you alone if I was your mom. [This can continue as needed.]

T: How is he doing?

C: He feels better.

T: Ask him if there are other scenes he wants help with, or would he like to leave the past behind and be with you in the present?

C: He wants to leave. [Often, addressing one or two scenes will remove what Stan calls the "key log" and clear the COEX.]

T: OK, where could he stay, if he's with you in the present?

C: I guess on my shoulder.

T: Does that work for him?

C: Yeah... He'd rather be in my heart.

T: Is that OK with you?

C: Yes.

T: OK, invite him there... How is he doing now?

C: Much better.

T: Do any of the other parts want to hang out there with him?

C: No. He's fine just with me.

T: Can he feel the burden of this worthless feeling that he has been carrying?

C: Yeah. It's kind of like that black hole feeling.

T: Would he like to release that burden?

C: Yes.

T: Ask him where he carries that burden of worthlessness in or around his body.

C: It's like a big weight pushing down on his shoulders.

T: Would he like to release that into fire, wind, light, water, or something else?

C: Light.

T: Help him by visualizing that burden being released from his shoulders into the light, and let me know when it is all gone.

C: OK. [A cognitive therapist might converse forever with a client's logical parts about this irrational belief in the client's worthlessness, while providing no relief at all for the part that carries the burden. If you want to debug the software, you need to specifically address the subroutine that contains the bug.]

T: Ask him if there are parts of him that got split off and lost in the past, that he would like to reclaim moving forward.

C: He can't find anything like that.

T: Anything else he wants to do right now?

C: No, he's fine.

T: Want to go back to the bingeing part?

C: OK.

We would next appreciate the bingeing part for how it took care of the little boy in the past when no one else was. We'd ask if it saw how the little boy was now being cared for by Self, and invite it to release the burden it carried of having to always keep the distressing feelings out of consciousness.

Then, that part could find a new role, possibly one of getting Self's attention when the little boy was feeling insecure, but instead of blending and causing the person to eat, it would just be sending a message to Self.

My IFS History

The first experiential model that I learned after becoming a licensed therapist was Heart-Centered Hypnotherapy. In this approach, we would perform an induction, have the client bring up a problematic issue, extensively identify the feeling in the body (does it have a location, size, color, temperature, texture, motion, etc.), and then use a linking regression to connect (COEX style) to an earlier unintegrated experience that was causing the unwanted reaction. But sometimes, after saying in my best hypnotist voice, "...and let me know when you find the source of that feeling," the response would be, "uhhh, I got nothing." Feeling the need for something to do in that case, I would ask people to dialogue with the feeling we had just connected to so deeply, and usually found that it would have a message for my client. For example, a tension in the chest that turned into a cough might say that it makes the person sick because she needs more time to relax.

That was the state of my "part art" when I attended Dick Schwartz's workshop on Internal Family Systems at the 2002 Psychotherapy Networker Conference. After his talk, I felt like someone walking into a new wilderness area, excited by my occasional discoveries, who then met a guy who handed me a detailed map of the terrain. Dick had classified the parts into categories, knew their various motivations, devised ways to work with them, and even invented new terminology to best describe what was going on. (Hmm... a new cartography of the psyche, inventing words: sounds a little like someone we know.) I read his book, Internal Family Systems Therapy, and began applying some of it with clients. In 2008, I attended another workshop with Dick, got inspired to reread the book, and began using the model extensively.

A short time later, as part of a breathwork weekend, I did a session in a cold pool. (I use the term "breathwork" in this article to refer to Holotropic Breathwork and other formats.) Afterward, while lying on a towel (recovering), my parts started talking to me, saying, "We hate this!" "Why do you make us do this?" "We keep trying to stop the process, and you just ignore us and push yourself to breathe more, even though we are scared." And they were right. My sessions typically involved some sort of effort to push past my defenses, and I often needed plenty of reminders to breathe. (I also noticed that even though I had requested these reminders, I often had an inner reaction that resented being told what to do and the implication that I wasn't doing it right.) With my new orientation to the inner family, I apologized to the aggrieved parts and began to explore their fears.

My next breathwork session was a Holotropic Breathwork format during Barbara Findeisen's STAR program. Before the session, I retired to my room and wrote a dialogue with my scared parts, further exploring their fears, promising that I would stay present to handle whatever came up, and asking their permission to go deeper. I was rewarded with one of my most profound sessions ever, where I convincingly relived my birth, encountering my extreme reluctance to make that transition, and being able to finally choose to be fully here on the planet.

Integrating Breathwork and IFS

Now, as I am continuing to explore the IFS model as a recent graduate of the Level 2 training and as an assistant in the Level 1 training, I am finding IFS and breathwork to be gratifyingly synergistic. They are both non-pathologizing—just as our work is guided by trust in the Inner Healer, IFS trusts in the presence of Self and that all parts are trying to help the system (though their methods may be misguided). An unofficial motto of IFS is "All parts are welcome," a mindset that should resonate with any Holotropic Breathwork practitioner. Symptoms, problems, and maladaptive behaviors are not resisted, but instead drawn out and explored.

While the two models share a basic stance, I see them as having different strengths. Breathwork is amazingly powerful at helping us escape the domination of defenses that would otherwise limit our experience, awareness, and self-knowledge for a lifetime. Added to an IFS practice, it can deepen the work dramatically and quickly. But from the IFS perspective, as my own protectors informed me by the side of the pool, breathwork can be perceived by defending parts as abusive. It lacks the safety that comes from letting protectors step aside only when they are ready.

IFS & Breathwork Continuum

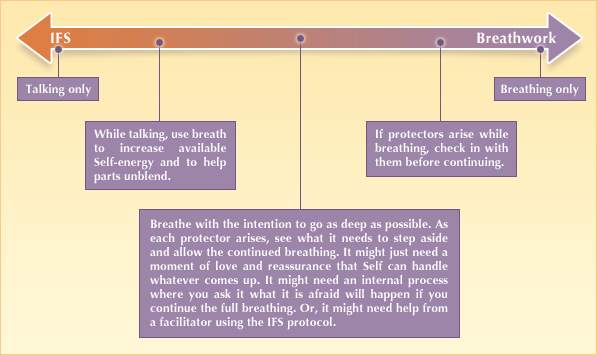

Having a deep appreciation for both models, I have been exploring ways to integrate the strengths of each, hoping that breathwork can deepen the IFS work, while IFS can bring integration and more safety to breathwork. In the following diagram, the second box represents bringing some breath to IFS, and the fourth box represents bringing an IFS perspective to breathwork. The middle box is a somewhat equal blending of the two:

The continuum

In an attempt to describe what happens in breathwork from an IFS perspective, I developed the following explanation.

Purposely increasing the breathing invites more Self-energy into the body, leading to a variety of possible experiences:

Parts unblend, and the participant experiences the attributes of Self.

The transpersonal Self is experienced as light, energy, bliss, or other spiritual manifestations.

Guides such as angels, power animals, or light are encountered.

The presence of Self from the breather and facilitator or sitter invites the emergence of exiles. The exiles find acceptance from Self. Also, the exiles express through the body to varying degrees, showing Self scenes from the past to be witnessed, felt, and healed.

Manager parts that have concerns about any of the above emerge, providing the opportunity to work with them. The process is especially effective at bringing to awareness managers that live in the body and serve to restrict the breathing and block the flow of energy. They can be unburdened of the need to inhibit the life force and experience that the result is not only safe, but also beneficial and enjoyable.

Over the past year, I offered several experimental workshops, some to IFS folks and one to a breathwork group. Each time, participants reported experiences that had not been available with their usual modality. IFS people found new parts, went deeper with familiar ones, developed relationships between parts, and experienced unburdenings that seemed more effective by being anchored in the body. Breathwork people interacted with and soothed parts that were afraid of the process, enabling deeper journeys afterward.

Last October, with the intention of introducing IFS folks to the power of breathwork, I presented a workshop at the IFS annual conference called "Experience the Potent Combination of IFS and Breathwork." (Thanks to Monique Lang, seasoned IFS practitioner and shaman, for her support in allowing this to happen!) The workshop began with a guided breathing exercise where participants were encouraged to notice any parts that objected to full breathing. The most common objections were from parts that feared the person becoming too big, powerful, or visible. Then, with a volunteer, I did a short demonstration of the approach described in the middle box in the Continuum diagram, during which the volunteer accessed a very scared exile that needed support from her. After this, the group did paired sessions, during which they were invited to verbally process if they wished, and almost all of them elected to stay with the breathing and work with their parts internally.

Despite having sessions of just 35 minutes, participants reported profound experiences. (I suffered deeply as I pared the music sets, but in a three-hour workshop, it is that or nothing. I find breathwork sessions to be like holograms—as you make them smaller, you still get the whole picture, just with less depth.)

I plan to offer more of this work, continuing to explore ways in which breathwork can empower IFS therapy.

IFS Contribution to Breathwork

So, what can IFS bring to a breathwork practice? As mentioned above, it is a wonderful integration tool. Whatever parts are activated by the breathing and music can be worked with after a session so that the system is restored to a more balanced and harmonious state. However, I am more interested in how IFS can help with protector parts that tend to resist the process.

Before continuing, I want to state my respect for the Inner Healer and that I would never give more credence to a practitioner's ideas of what should happen over any direction that the Inner Healer might choose. But I do believe there may be room for some facilitator assistance in between the moment the participant begins breathing and hearing the music (let's call it Time A) and the moment when the participant has access to the Inner Healer (Time B). Though Time B is vague and indeterminate, presumably it is after Time A. Perhaps Stan is referring to Time B when he advises us to "breathe until you are surprised." It is my belief that a facilitator who can stay grounded in Self-energy (by preventing blending from his or her own parts that need to "do something," know the answer, or take care of people) can be of assistance in between Times A and B without violating the holotropic ethos.

What is happening between Times A and B? If all is going well, the breathing and music are working to facilitate a holotropic state of consciousness, and all protector parts trust the process and step aside. But what about parts that aren't ready? We have seen them interfere in all kinds of ways:

Parts physically restrict the breathing so that it never becomes fast and deep enough to access the holotropic state.

Thinking parts won't step aside, preventing a deep experience.

Compliant parts try to create the appearance of deep breathing while not much air is actually moving.

Parts with a trauma history keep the breather dissociated from her body.

Parts blatantly stop the process.

As these parts are flushed out by the breathing, IFS offers valuable tools to help them. We can connect with them and honor their fears. We can appreciate them for how they protected us in the past. We can let them know that we hear their warnings about the process not being safe. We can understand why they believe it is unsafe to come into the body. We can witness scenes from the past where they took on the burdens of protecting us by inhibiting our energy and reducing our vitality. We can help them recognize, immediately or gradually, that things are different now. We can make them aware of Self-energy that is present to handle whatever might come up. After this, when they are ready, they can willingly step aside and allow the journey to continue.

Contrast this to the following passage from Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy:

Additional reasons for intervention are situations when some of the breathers refuse to continue because they experience too much fear or unpleasant physical symptoms. Then the facilitators try to give them reassurance or offer relieving bodywork to make them more comfortable. Once these reluctant breathers are "in process," it is essential to keep them in the room and support them until they reach successful resolution of their sessions. (p. 67)

Without a parts perspective, this kind of intervention is completely compassionate and provides supportive facilitation. But imagine you were a part that took on the job of protecting the person from a traumatic, life-threatening experience, and your only mission in life was to make sure this never happened again. You can feel that the accelerated breathing is bringing this dreaded, dangerous experience back now. Instead of just reassurance, which would probably feel like logical parts pressuring you, wouldn't you rather be understood in your mission first? After your message is received, you might be more open to seeing how circumstances have changed since you took on your job, allowing you to relax. In addition, because you would no longer be opposed to the process, nobody would have to keep the breather in the room.

Similarly, on p. 196, the Grofs state, "When the fear of letting go becomes an issue in Holotropic Breathwork, the first step is to convince the breather that the fantasies associated with it are unsubstantiated." Often, the conscious, rational part of the breather, which is usually the part that is talking to you, already knows this. Being able to directly access the parts that don't already know this makes the conversation much more fruitful.

Besides techniques to help resistant parts truly step aside, I believe IFS can create an extra level of safety in breathwork. Like most of you, I have a deep trust in the inherent safety of the process. I so appreciate the extent of training provided by GTT, where we get to repeatedly find ourselves in situations wondering, "How are we going to get out of this one?", only to find that the Inner Healer always finds a beautiful resolution and saves the day.

But do we really know all of the ramifications of what we are doing? One of the main complaints that I have heard about Holotropic Breathwork is that we will breeze into a city, conduct a weekend workshop, and then leave, unaware of the aftermath. Unfortunately, we have not acquired the resources to adequately study the experiences of participants post-breathwork. Given that we often do offer this experience without much follow-up, it behooves us to find ways to minimize any possible backlash.

How many people have approached you at the end of a workshop and said, "That was amazing, one of the most profound experiences ever—you will DEFINITELY see me again!" How many of those people have you never seen again? Or am I the only one who experiences this? I wonder what keeps them away. Could it be that parts that had been disabled by the breathwork process have since reasserted control? Because these protective parts were not sufficiently prepared for the experience, are they now determined to never let it happen again?

In talking to Dick Schwartz about breathwork, his main caution is about trauma survivors. These people often have parts that, for good reason, protect the person from extreme experiences by dissociating, or taking Self out of the body. They can find it extremely threatening when the breathing feels like it is dragging Self back into the body. These parts, in particular, need to have their concerns addressed and willingly grant permission before the breathing continues.

In the chapter "Breath and Consciousness: Reconsidering the Viability of Breathwork in Psychological and Spiritual Interventions in Human Development" in a collection titled Body, Breath, and Consciousness: A Somatics Anthology, Peter Levine, a trauma therapist who developed Somatic Experiencing, writes (along with Ian Macnaughton):

In the West, there are a number of new approaches to working with breath. One of the latest involves the use of "high energy" hyperventilation, often described as the use of Eastern methodology translated into Western terms. Examples of this include the Grof Holotrophic (sic) Breathwork, some types of rebirthing, and certain Western versions of shamanic practices.

The authors of this paper have some concerns about such kind of "high energy" hyperventilation. (p. 369)

They go on to elaborate their perspective, cautioning, "The sudden introduction of vast quantities of energy, as happens during intense hyperventilation and catharsis, can destabilize a person's ‘self' organization." Similarly, in the same book, Lisbeth Marcher, a Danish body psychotherapist, states:

I don't disagree with Reich's concept of pulsation, but I don't think the best way to get to it is through turning on the tap full-blast and seeing what happens. To me, that is not an integrated therapy. Essential parts of the self get split off in that kind of work. I see the same problem with Stan Grof's Holotropic Breathwork.... I am concerned about what therapy is—what actually helps a person change their life—not just have an intense, unintegrated experience. (pp. 95–96)

When I first read these passages many years ago, I felt defensive and decided that they had not had enough experience around breathwork to recognize our consistently positive outcomes. But "positive outcome" is often just a judgment call. I remember friends who sold Shaklee nutritional products telling someone it was good that he became sick after taking the products, as it meant he was detoxifying. And there could be truth to that. In our work, we often see things get worse before they get better. But perhaps we should be more aware of how others in the field are viewing our work. As we move forward with research projects, we will need results that the world of empirical research will judge to be "positive outcomes." A psychospiritual crisis that we trust will be eventually resolved by the Inner Healer is likely to be judged a negative outcome.

In explaining their strategy for avoiding this, Levine and Macnaughton state, "When we, as therapists, intervene to remove some of this defensive armor, it is essential that other more functional resources are found for the individual... The person needs information, preparation, experience, and pacing through developmental layers before these experiences can be integrated as part of their developmental shift toward realizing their full potential.... The process of using small interventions, assessing the impact, and reassessing what to do next, is a process we term titration..." Bringing an IFS approach to breathwork would answer their concerns, as the deepening process could proceed step by step, with each protector part feeling safe enough before the next layer of material is accessed.

I would like to share some words from an IFS practitioner after her first breathwork session:

The fear I mentioned to you that I experienced during the breathing, came from protective parts that felt unable to protect. The breathing and the music, which was EXTREMELY evocative for me, created an intensely jolting experience that rendered my protectors totally powerless, and that was very scary. My protectors are usually very peaceful and cooperative. My protectors aren't extreme and they trust my Self. When I do my work, they are very willing to step aside when asked to do so, and allow me to explore and experience. But I guess they need to be acknowledged and allowed to come to trust the situation and relax naturally.

Unlike "traditional IFS," this time they weren't asked for permission, they weren't given a respectful invitation to step aside yet to stay close, in case they'll have the need to jump back in. Their experience was that they were almost forcefully removed without being given a choice. I felt assaulted by the intense combination of the physical experience and the music. I felt I had no control over my body and all of that was very new and (therefore?) very scary.

In fact, I know that I had a choice the whole time—I could have just stopped doing the breathing, I could have left the room, etc. But I had parts who wanted to see it through, there was probably enough Self to be curious about this new experience and where it could take me, and enough courage to stick with it, in spite of the fear.

But there was definitely a point in the process where I didn't feel I had a choice, I wasn't cognizant of it. I was in the dark, my protectors paralyzed with shock and a loud "what is happening to me?!" was sounding inside...

As we would expect, despite this difficulty, she reported an "amazing experience," going on to say, "my experience at your workshop was very meaningful. I connected with a little girl I didn't connect with for many years and was able to unburden her through the intense crying (tears she was never able to shed in real time), and show her love and appreciation she so deserves. She stayed with me and in the days that followed I felt an energetic shift in me, like there was more space inside, lightness, relief and more joy." Nevertheless, she retains serious concerns about the safety of the process. Perhaps other participants are having similar experiences without the insight to describe them to us so clearly. What if we could have the best of both worlds?

One other thing: In addition to helping with parts that resist the breathwork process, the IFS framework might contribute in another area. Have you ever worked with someone who seemed to cycle in his sessions, apparently visiting the same traumatic material over and over, without reporting any resolution or a useful shift in his life? Earlier, I proposed that the presence of Self in the breathwork process invites the emergence of exiles, which sometimes express through the body, so that they can find witnessing, acceptance, and support from Self. If, while this process is occurring, dissociative protectors feel threatened and whisk Self out of the body, the healing would be disrupted.

If this explanation for the lack of a positive outcome is valid, then some kind of intervention to bring back Self-energy into the body might be helpful. Perhaps a facilitator could provide gentle reassurance or even hold the breather's feet to invite Self to return. I understand that this idea violates our tenet to trust the Inner Healer rather than intervene in the breather's process and opens the door to facilitator parts that want to save the day. Perhaps people smarter than I can find a solution for this dilemma. A minimal boundary could be to get prior permission for such an intervention; another approach could be to let the breathing session play out, and then use IFS to address the concerns of the dissociative parts in preparation for future sessions. But, at least, we should be curious about outcomes that are not optimal and consider possibilities for increasing Self-energy.

In closing, I want to speak for a part of me that fears an angry reaction from people who might feel I am attacking or criticizing Holotropic Breathwork. I believe that our work, just as it is, is one of the best things happening on this planet. I would love more people to benefit from it, and my hope is that bringing in some of the ideas discussed here can help make that happen. Perhaps we can minimize the possibility of backlash and improve our reputation for safety, while facilitating even more positive outcomes and bringing more people back to continue their breathwork journeys.

This article originally appeared in The Inner Door Vol. 23 Issue 1 (February 2011), published by the Association for Holotropic Breathwork International.